Cover image used with licensed permission. Article © 2011 by the Center for Endometriosis Care/Ken Sinervo MD, MSc, FRCSC. All rights reserved. No reproduction permitted without written permission. Revised since original publication and current as of 2023. No external funding was utilized in the creation of this material. The Center for Endometriosis Care neither endorses nor has affiliation with any resources cited herein. The following material is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Note: we are aware this original article has been duplicated in large part elsewhere by another source without permission or proper attribution. Such duplication does not indicate endorsement by, affiliation with, or approval of the CEC.

Extrapelvic Endometriosis: Sciatic

Endometriosis is a disease characterized by the presence of tissue somewhat resembling the lining the uterus found in other areas of the body. While the disease commonly develops on the pelvic structures including the bladder, bowels, intestines, ovaries and fallopian tubes, it has also been found in distant locations. In fact, endometriosis has been found in virtually every organ system. The exact prevalence of extrapelvic endometriosis specifically by site remains largely unknown, however, due to the small number of well-designed epidemiological studies. Nevertheless, the disease has been documented in the spleen; rectus abdominis muscle (“abs”), the brain and eyes, in surgical scars, the upper and lower respiratory system, diaphragm, pleura and pericardium, abdominal wall, thorax and nasal mucosa and countless other locations. Though rare, intrahepatic endometriosis and disease even as far remote as the gastrocnemius have been reported. Extrapelvic disease, though less common, can manifest in a variety of ways, e.g. catamenial pneumothorax when affecting the lungs. One consideration for some patients who may present with specific, regional symptoms is sciatic endometriosis.

Few if any laboratory tests are valuable in the endometriosis diagnostic spectrum in general, as markers i.e., CA-125 have very low specificity and sensitivity. Imaging tests (MRI, ultrasound, CT scan) can be more specific and helpful (particularly in the surgical planning stage), but it is difficult if not impossible to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of endometriosis based on symptoms and tests alone. Likewise, though some may opt for a clinical ‘diagnosis’ through application of hormonal therapy, such approach is far from accurate. True confirmation can only be obtained through surgical biopsy. Therefore, suspected extrapelvic disease should never be dismissed out of hand.

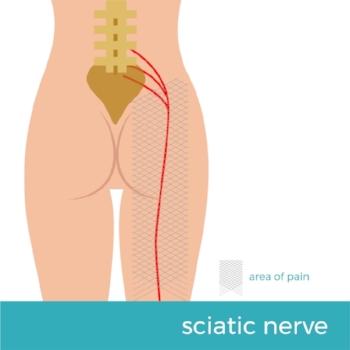

Used with licensed permission. Credit: (c) Paveugra 2018.

Sciatic endometriosis is not abundantly common – but it should be included in the diagnostic approach to pain and symptoms affecting the sciatic nerve distribution. One of the first cases of biopsy-confirmed sciatic endometriosis was described by Denton & Sherill in 1955. Since then, many additional cases have appeared in the literature. Symptoms that may lead to suspicion of sciatic disease may be predominantly left-sided, though infiltration of the pelvic wall and somatic nerves causing severe neuropathic symptoms due to endometriosis infiltrating the right sciatic nerve has also been documented.

Pain may be associated with menstruation in those with periods and begin just before menses, lasting several days after end of flow and be accompanied by motor deficits, low back discomfort radiating to the leg, foot drop, gait disorder due to sciatic musculature weakness, cramping and/or numbness radiating down the leg, often when – but not limited to – walking, especially long distances, and tenderness of the sciatic notch. There may also be positive Lasègue’s Sign (an indication of lumbar root or sciatic nerve irritation in which ‘dorsiflexion of the ankle of an individual lying supine with the hip flexed causes pain or muscle spasm in the posterior thigh’ [Kosteljanetz et al]). There is almost always a history of pelvic endometriosis. Left untreated, sciatic endometriosis may cause nerve damage.

Physical examination may reveal various neurological deficits involving the sciatic nerve rootlets. There may be localized tenderness over the sciatic notch, but this is not always found. Pelvic examination may also even be normal. Imaging can aid in diagnosis, though ultimately a surgical diagnosis is indicated. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to minimize the damage. While sacral radiculopathies (pudendal, gluteal pain), vascular entrapment or sciatic neuralgia may be at the root of symptoms for some individuals, in patients with sciatica of unknown genesis and/or suspicion of pathology such as endometriosis, laparoscopic exploration of the sacral plexus and/or sciatic nerve is advisable.

Sciatic endometriosis is generally treated the same way as pelvic disease: preferably gold-standard surgical eradication (excision). When not possible, a course of medical therapy may suppress symptoms until such time as the patient can receive proper surgical intervention with a skilled, minimally invasive pelvic surgeon who has vast experience in highly complex cases of endometriosis. Physical therapy with a skilled PT specializing in endometriosis and CPP can be very helpful as well.

It is very important to understand that not every patient with symptoms relating to the lumbosacral plexus or proximal sciatic nerve bundle will actually have sciatic endometriosis, as there can be several differential diagnoses. However – endometriosis can be a real (albeit less common) cause of nerve injury and symptomology. This extrapelvic manifestation of the disease must be considered in the differential diagnosis of those with symptomatic presentation, particularly if a history of endometriosis or chronic pelvic pain is present.

If you or someone you love suffers (or thinks they may be suffering) from endometriosis, we’d be honored to lend our expertise. Please click here and here to learn more about the CEC’s services.